It is estimated that one in ten women of reproductive age suffer with this debilitating illness and yet it takes on average seven years for a diagnosis to be made. Is it any wonder that sufferers of this poorly understood reproductive disease are drained by the time they visit a nutritionist for help?

What do we know about endometriosis?

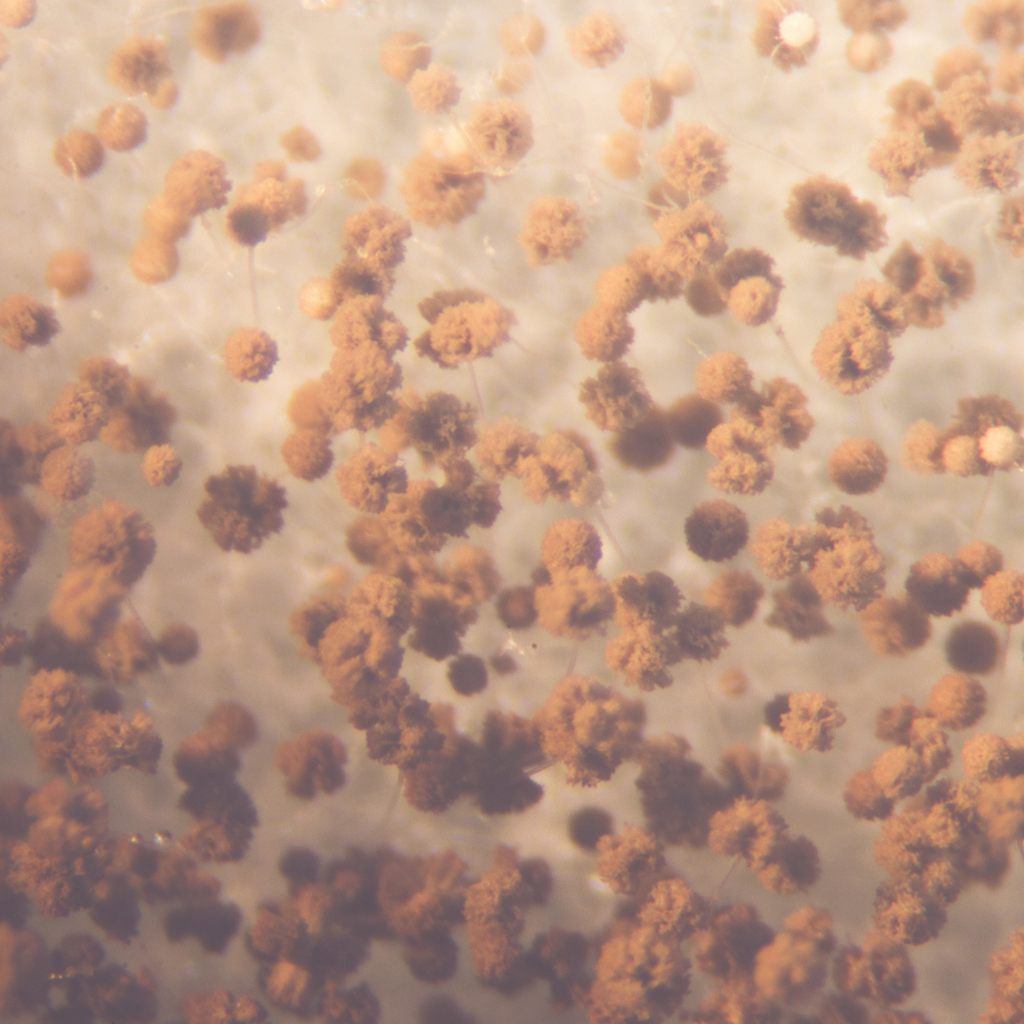

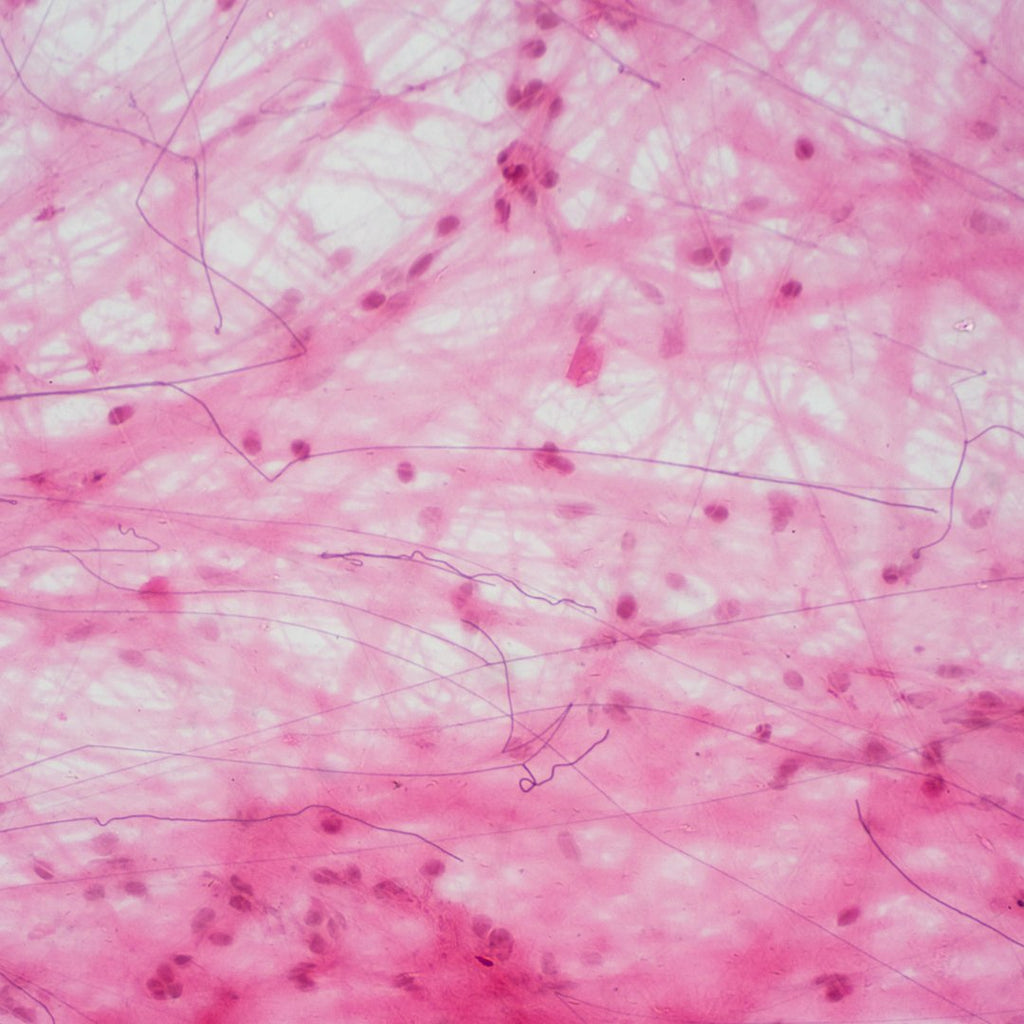

Endometriosis is classed as an oestrogen-dependent inflammatory condition whereby endometrial tissue, the tissue found on the inner lining of the uterus, is found outside the uterus in areas such as the ovaries, the fallopian tubes, the peritoneum and the rectal-vaginal septum. In some cases endometrial tissue has also been found outside the reproductive organs in the bladder, bowel and intestines and, in rare cases, it has further migrated to areas such as the lungs.

The reason this occurs is still unknown, however there are many theories for this, including (the original theory) retrograde menstruation whereby the endometrial tissue is believed to flow backwards during menstruation and plant itself outside the uterus. This has been superseded more recently with suggestions that there is a genetic cause, as it is not uncommon to see more than one sufferer in a family. Immune system dysfunction has also been hypothesised to play a role due to immunological defects being present, although it is not known whether this occurs as a consequence of endometriosis rather than as a causal factor. Metaplasia of tissue, environmental factors and lymphatic or vascular distribution are other theories; overall, though, there is currently no firm evidence of the exact cause of the condition, which is likely to differ in each case.

As a result, it is unsurprising that there is also no known medical cure for endometriosis at this time. The main treatments for endometriosis are focused on suppression of menstruation, using GnRH analogues to stop the production of oestrogen; inserting the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system to secrete a constant supply of progesterone; or danazol to decrease the production of hormones in the ovaries. The most effective treatment, though, appears to be laparoscopic surgery. NSAIDs are often prescribed for pain management, however there is limited evidence for their effectiveness which may be due to misuse. (1) As this condition only presents in women of reproductive age, women with severe, persistent symptoms are often advised, and opt, to have a hysterectomy; however, this has not been successful in alleviating symptoms in all cases.

Understanding endometriosis and when to refer

There are four stages of endometriosis and patients can vary from stage I, with smaller lesions and inflammation around the pelvic area, to stage IV, where the lesions infiltrate tissue of the pelvic organs, which may lead to distortion of the structure.

The main symptom of endometriosis is pelvic pain which can be extremely debilitating and arise at several points in the menstruation cycle, such as before, during or after menses and ovulation. Associated symptoms include dysuria, dyspareunia, pain in the lower back and bowels, constipation, diarrhoea and heavy or irregular bleeding. As many of these symptoms are common in other conditions, it is not unusual for a woman with endometriosis to be misdiagnosed with conditions such as ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, fibroids, cystitis and pelvic inflammatory disease. A diagnosis of endometriosis can only be made via a laparoscopy and biopsy; unfortunately this is not usually the first port of call for a woman seeing her GP with the above symptoms, so it is important to be aware of these key indicators to be able to identify and make an informed referral for suspected endometriosis.

Applying nutrition support

Despite the currently bleak state of medical care for this condition, there is a wealth of research suggesting that both diet and lifestyle interventions may be successful in preventing and managing endometriosis progression. The following steps are safe and scientific ways to support your clients with both suspected and confirmed endometriosis.

Diet

Anti-inflammatory diet

Research suggests that women with endometriosis consume less vegetables and polyunsaturated fatty acids, whilst also having a higher intake of red meat, coffee and trans-fats than women who do not have the condition. (2) Inflammation plays a huge role in the aetiology of endometriosis, therefore reducing intake of red meat, dairy products and eggs (as sources of pro-inflammatory arachidonic acid (AA)) and increasing sources of anti-inflammatory polyunsaturated fatty acids (such as pumpkin seeds, walnuts, hemp seeds, dark green leafy vegetables and oily fish) is recommended. Furthermore, stearic acid also induces aromatase activity (the enzyme responsible for the aromatisation of androgens into oestrogens), which is already elevated in those with endometriosis, thus reducing intake of dairy, grains, red meat and pork should work two-fold by helping to reduce both inflammatory AA and stearic acid intake. (3)

Antioxidant rich

A diet rich in antioxidants is recommended as they have been shown to reduce chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhoea and dyspareunia, and assist the immune system which is dysregulated in women with endometriosis (4, 5, 6). Additionally, flavonoids and polyphenols such as resveratrol, curcumin and EPCG, have been shown to inhibit aromatase enzyme activity (3, 7). Furthermore, vitamins A, C and E have also been shown to reduce oxidative stress markers and increase antioxidant enzyme activity in women with endometriosis. (8, 9)

Indole-3-Carbinol

As aromatase activity is high in those with endometriosis, increasing intake of foods rich in Indol-3-Carbinol (I3C), such as broccoli, cauliflower and cabbage, may be of benefit due to their aromatase inhibition activity. I3C has also been shown to promote intestinal immune function against the negative effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals. (10)

Supplementation

Vitamin D

Women with endometriosis have been shown to have dysregulation of vitamin D receptors, and animal studies have shown that treatment with vitamin D improved lesions. (11, 12) This suggests it is advisable to have vitamin D levels checked and supplement accordingly to ensure optimal levels are maintained throughout the year. Igennus Pure & Essential Daily Vitamin D3 contains 2000IU, bioavailable cholecalciferol as a 1-a-day supplement to ensure optimal vitamin D3 levels are maintained throughout the seasons.

EPA omega-3

Consumption of fish oil has been shown to reduce symptoms of dysmenorrhoea. (13) EPA is the precursor to anti-inflammatory eicosanoids and can directly displace pro-inflammatory arachidonic acid for metabolism. Supplementing with a product such as Pharmepa Restore, a pure EPA, highly bioavailable and concentrated omega-3 product, will quickly elevate EPA levels and help balance the AA to EPA ratio to provide therapeutic anti-inflammatory support.

Curcumin

Curcumin is a potent anti-oxidant and has also been found to inhibit aromatase activity. Supplementing with an optimised curcumin, such as Longvida, overcomes the poor bioavailability of most curcumin and turmeric sources. Longvida’s patented lipid technology provides 285x greater bioavailability (AUC) to increase plasma levels 65x more than standard turmeric and deliver 7x longer lasting action.

Lifestyle

EDCs

Endocrine disrupting chemicals have been shown to increase the risk of endometriosis, therefore a prudent and necessary step in any hormonal condition support plan would be educating your client on the negative effects of dioxins, POP’s and PCB’s, which are found widely in cleaning products, environmental chemicals and personal care products, including cosmetics, and how they can be avoided. is (14, 15) This link is a useful place to start and includes a downloadable PDF that can be sent to clients.

Exercise

Regular exercise is important for protecting the body from inflammatory diseases, as it increases anti-inflammatory cytokines and anti-oxidant activity. However, exercise may be very difficult for many with endometriosis due to the high levels of pain they experience. Discuss with your client the types of exercise they enjoy and recommend something gentle, such as walking or swimming as a good place to start. (16) Weight bearing exercise such as resistance training is important to prevent loss of bone mineral density associated with hypo-oestrogenic medication.

Sleep hygiene

Melatonin has been shown to reduce daily pain and dysmenorrhoea in women with endometriosis and, whilst we are unable to obtain supplemental melatonin here in the UK, there are steps you can implement to naturally support melatonin levels. (17) Maximum exposure to natural sunlight may help to boost levels so suggest an early morning walk. Emphasis needs to be placed on good sleep hygiene so ensuring a dark room at night, no exposure to artificial lights for an adequate amount of time before bed and implementing a sleeping pattern of going to bed early enough to ensure a full night’s sleep is obtained may help in the regulation of melatonin.

Summary

Endometriosis is still very poorly understood by the mainstream medical profession, and many mis-diagnoses are made each year. Taking time to listen to your client and understanding how the condition affects their everyday life, and helping them understand the steps needed to support their unique experiences and needs is as important as putting together a nutritionally dense, tailored support protocol. Researching a local support group to refer your client to, which can be found on the endometriosis UK website, is a great way to put clients in touch with other people who understand the daily frustrations and agonising pain they face, and get the ongoing support needed. Removing drivers of endometriosis and putting in place strategies to support the optimal functioning of the pathways involved in its onset and exacerbation can provide significant relief and even reversal of this otherwise debilitating and chronic condition.

References

- Brown J, Crawford TJ, Allen C, et al.(2017). ‘Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain in women with endometriosis’. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , (1).

- Parazzini F, Viganò P, Candiani M, et al. (2013). ‘Diet and endometriosis risk: A literature review’, Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 26 (4), pp. 323-336.

- Subbaramaiah K, Sue E, Bhardwaj P, et al. (2013). ‘Dietary polyphenols suppress elevated levels of proinflammatory mediators and aromatase in the mammary gland of obese mice’, Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa.), 6 (9), pp. 886-97.

- Santanam N, Kavtaradze N, Murphy A, et al. (2013). ‘Antioxidant supplementation reduces endometriosis-related pelvic pain in humans’, The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine, 161, (3), pp. 189-95.

- Sesti F, Capozzolo T, Pietropolli A, et al. (2011). ‘Dietary therapy: a new strategy for management of chronic pelvic pain’, Nutrition research reviews, 24 (1), pp. 31-8.

- Wei C, Mei J, Tang L, et al. (2016). ‘1-Methyl-tryptophan attenuates regulatory T cells differentiation due to the inhibition of estrogen-IDO1-MRC2 axis in endometriosis’, Cell Death and Disease, 7 (12), p. e2489.

- Balunas, B. Su R. (2012). ‘Natural Products as Aromatase Inhibitors’, Anticancer Agents Med Chem, 29 (6), pp. 997-1003.

- Mier-Cabrera J, Aburto-Soto T, Burrola-Méndez S, et al. (2009). ‘Women with endometriosis improved their peripheral antioxidant markers after the application of a high antioxidant diet’, Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 7 (1), p. 54.

- Mier-Cabrera J De la Jara-Diaz J, Perichart-Perera O, et al. (2008). ‘Effect of vitamins C and E supplementation on peripheral oxidative stress markers and pregnancy rate in women with endometriosis’, International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics, 100 (3), p. 252.

- Hooper L (2011). ‘You AhR what you eat: Linking diet and immunity’, Cell, 147 (3), pp. 489-491.

- Sayegh L, Fuleihan G, Nassar (2014). ‘Vitamin D in endometriosis: A causative or confounding factor?’ A Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, 63 (1), pp. 32-41.

- Lerchbaum E, Rabe T. (2014). ‘Vitamin D and female fertility’, Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology, 26 (3), pp. 145-150.

- Hansen S, Knudsen U. (2013). ‘Endometriosis, dysmenorrhoea and diet’, European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 169 (2), pp. 162-171.

- Cooney M, Buck Louis G, Hediger M. et al. (2010). ‘Organochlorine pesticides and endometriosis’, Reproductive Toxicology, 30 (3), pp. 365-369.

- Williams K, Miroshnychenko O, Johansen E, et al. (2015). ‘Urine, peritoneal fluid and omental fat proteomes of reproductive age women: Endometriosis-related changes and associations with endocrine disrupting chemicals’, Journal of Proteomics, 113, pp. 194-205.

- Bonocher C, Montenegro M, Rosa e Silva J, et al. (2014). ‘Endometriosis and physical exercises: a systematic review’, Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 12 (1) p. 4.

- Schwertner A, Conceicao-Dos-Santos C, Costa G et al. (2013). ‘Efficacy of melatonin in the treatment of endometriosis: a phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial’, Pain, 154, pp. 874-881.